One of the milestones of Italian pasta history is Bartolomeo Scappi’s capon tortelletti from his cookbook Opera (1570). They deserve to be mentioned on par with Renaissance art as a yearning to express the sublime.

Tortelli, tortelletti, tortellini. All of these names derive from the base form “torta” - which simply means cake. These three indicate the size or delicacy of the pasta form - elli - etti - ini. Tortellini have gone on to mean one very specific pasta shape and filling combination. Tortelletti is no longer in use, and tortelli tends to refer to round ravioli rather than square. Today, the word tortelli has been eclipsed by the word ravioli, although at one time in Italy, ravioli referred to the entity inside the wrapper - and the pasta itself was considered an optional.

Like most historical recipes, this one is not without its mysterious moments. But for a culinary historian, it calls out much in the way that restless minds are drawn to the NYTimes crossword puzzle. It is a nut begging to be cracked.

Let’s proceed to our purpose.

Whaddya do about udders?

As I am not cooking for the Pope and his entourage, I felt that a half recipe would allow me to trial it, eat some, and have some left to freeze. The main ingredient is capon breast. Scappi specifies two, so the full breast of one bird, but, unlike most of the other ingredients, he is not explicit about the weight. Given the flavor potency and fat content of the other ingredients, a balanced filling hinges on the proportion of capon included, as the delicate white meat will temper the onslaught of the spices and offset any greasiness. I settled on 300g of deboned meat including the skin.

The skin is not specifically included in the recipe, but its presence would resolve a couple issues. The recipe calls for chicken fat as well as a small but significant amount of cow udder. Udder lends a luxuriously soft, velvety texture to the filling. Simply dispensing of it as an optional would upset the balance of what is clearly intended to be a sumptuously unctuous filling. But at the same time, I cannot expect anyone to go on a wild udder chase. The inclusion of the skin would cover both the chicken fat and the need for a blubbery (in the good way!) support that lent a modicum of substance.

Beef marrow, too, plays a supporting role in the way the filling melts in your mouth when released from its casing. But with a cautious eye on the temperature requirements, I decided to bake it first, in the bone, to get it through the required 145°F (62.8 °C) internal temperature check point. I included all of the oils that seep out during the baking which are touted as health-giving. Baking also deepened the flavor.

Sugar and spice

The sugar content in Medieval and Renaissance Italian recipes brings up an issue about the conflict of taste and expectations for the modern palate. Scappi was the personal chef to the Pope. As such, he was in a sense obliged to lean heavily on elements that would put his patron in a good light with guests. Sugar and spices (actually, at this juncture, sugar was considered a spice) were today’s caviar and champagne. Both were dosed liberally as a demonstration of power, sophistication, and prowess. The food represented the master.

Most households, I daresay, would not have enjoyed the budget of the Holy See and would clearly have had to make do with less sugar and spice. When I make desserts, I almost invariably use less sugar simply because that is how I prefer it. A recipe is only ever an indication for how one chef feels s/he has achieved a successful outcome in the context in which they operate.

I have left the sugar as is prescribed by Scappi so that you might adjust it as you see fit. Given the quantity of sugar that is included in other recipes of the era, here Scappi has actually been rather moderate. The result is a filling that speaks of the Renaissance appreciation for sugar as a means of refining a dish, rendering it regal. It is not cloying and remains under the threshold of sweetness that would lead us to consider this a misguided dessert. Interestingly, Scappi’s concern in this recipe is that filling not be too salty - even though he never mentions adding salt.

A refined eggless dough

Finally, there is the question of the dough. Maddeningly, the instructions are, “get a rather thin sheet of dough made with flour, rosewater, salt, butter, sugar and warm water, and out of that pasta jagger or dough cutter, cut out large or small tortellini.” Scappi clearly felt he could dispense with the measurements for a simple pasta dough, as everyone knows how to do that. My measurements are below if you want to rely on my experimentation.

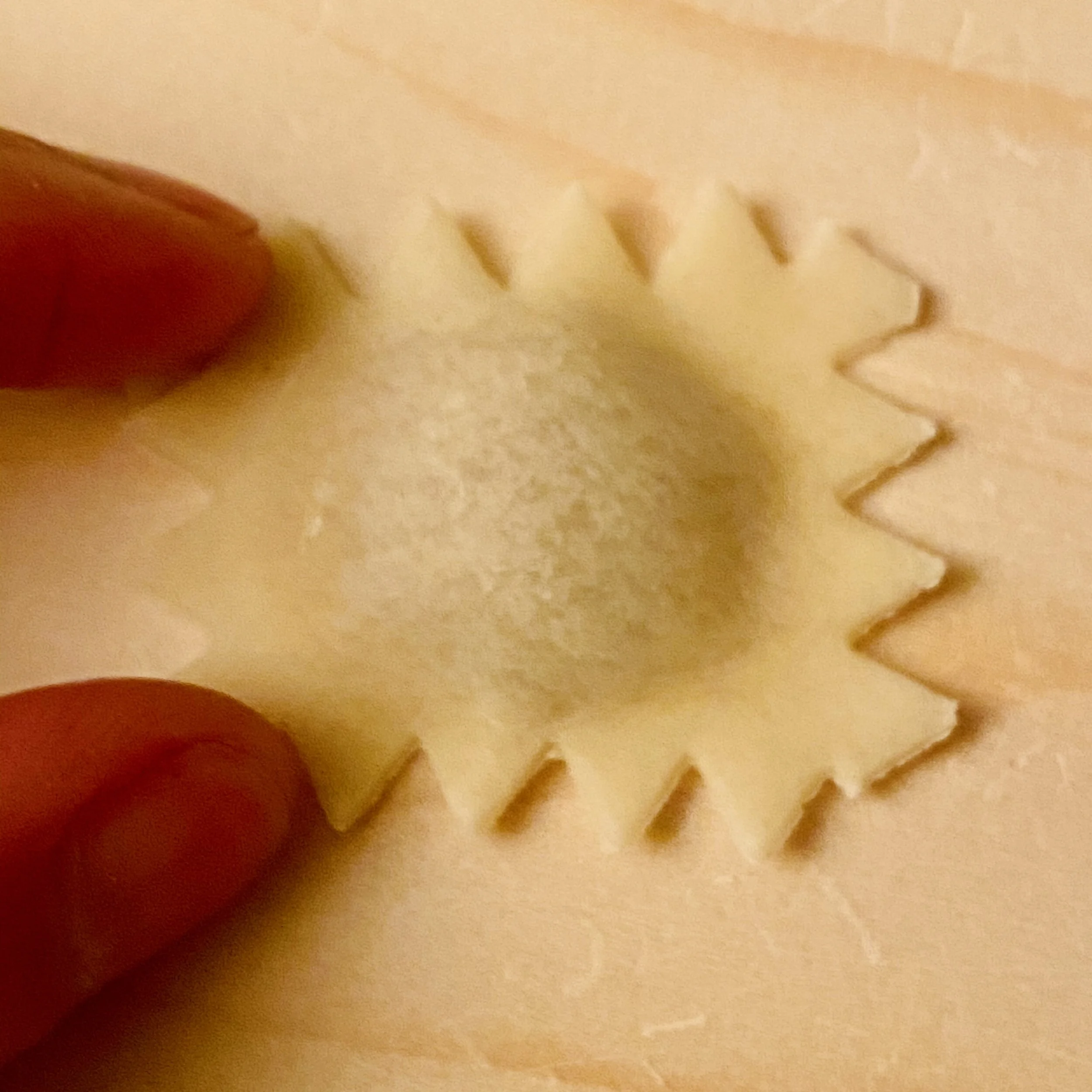

I did two trials of this dough. In the first I rolled it out very thin and making dainty little tortellini.

But I was not satisfied with the overall experience of the casing / filling relationship. The dough needed to be more substantial to support the richness of the filling.

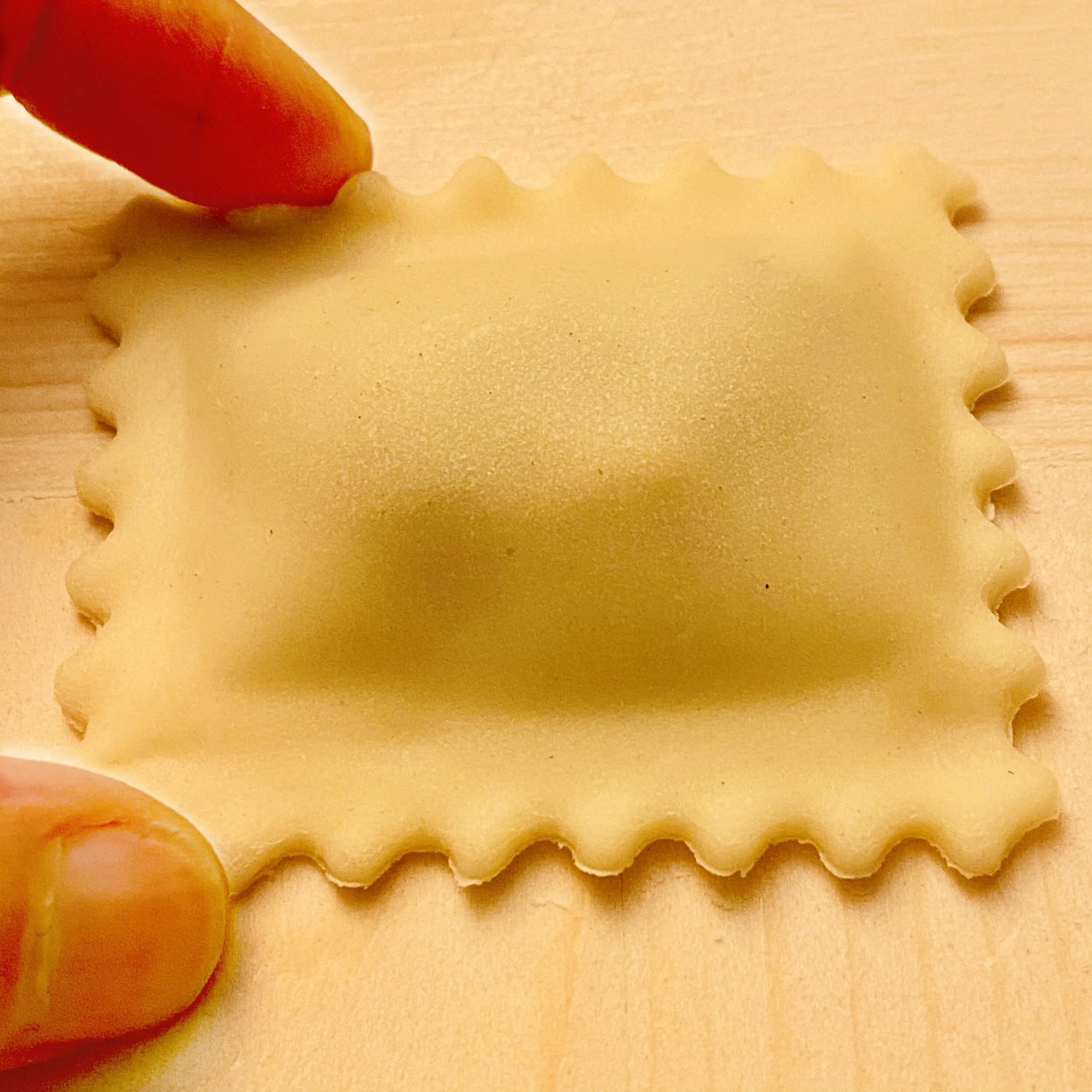

I went back to the drawing board and tried using the same dough but rolled thicker. I also cut the tortellini larger, as Scappi didn’t seem to mind what size they were.

…and they were just right.

TO PREPARE TORTELLINI WITH CAPON MEAT

Serves 10

INGREDIENTS:

[dough]

600g flour

60g softened butter

2 tbsp sugar

2 tsp salt

120ml rosewater

120 ml warm water

[filling]

300g capon (or chicken) breast meat, cooked with skin

150g beef bone marrow, baked and removed from bone

150g fresh ricotta

2 egg yolks plus 1 whole egg slightly beaten

75g fine white sugar

1tbsp cinnamon

1 tsp freshly ground pepper

1/2 tsp ground cloves

1/2 tsp ground nutmeg

1 good pinch saffron

(for best flavor, use freshly ground spices)

1 tsp finely chopped mint

1 tsp finely chopped fresh marjoram

other herbs, optional according to taste

40g finely chopped currants or raisins

1 tsp salt

2 liters of meat broth for cooking

[garnish]

cinnamon sugar

grated parmesan cheese

INSTRUCTIONS:

Put all of the dough ingredients into a stand up mixer with a dough hook and mix until combined.

Turn the dough out onto a counter and knead by hand for 10 minutes. Wrap it in plastic and let it rest for 30 minutes.

In whatever sort of machine you prefer, grind the chicken and bone marrow.

Transfer to a medium bowl and add all of the other filling ingredients.

Roll out the dough either using a pasta machine - not set at the thinnest setting - or by hand with a mattarello and spianatoia.

Put the filling into a pastry pouch and apply the filling to half or the dough so that it is 2 x 3cm with 2 centimeters between each dab.

Wrap the half of the dough without the filling around the rolling pin to assist you in placing it over the dabs. Press between each tortello and remove the air, using a pin if needed.

Cut with a pasta wheel.

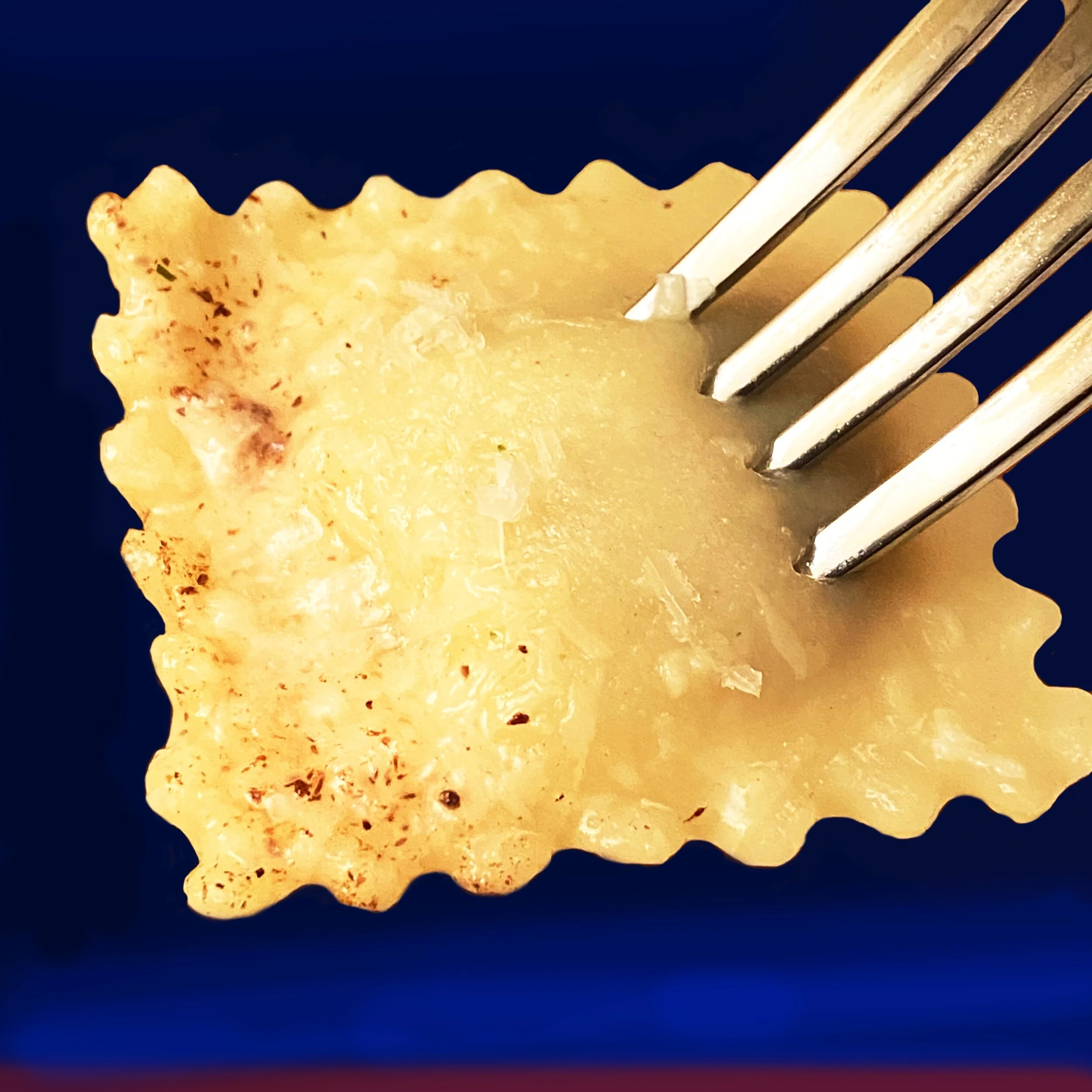

Bring the broth to a boil and place the tortellini inside the pot. Do not overcrowd.

To serve, plate the pasta, add 2-3 tablespoons of hot broth to each plate, then sprinkle with cheese and cinnamon sugar.