To call mostaccioli ‘crackers’ would give the impression that they were light and crisp, whereas the word ‘cookie’ carries immediate associations with a sweet dessert-like treat. Neither accurately captures the essence of this food. Perhaps mostaccioli are best described as hard, dry, spiced biscuits that are neither decidedly sweet nor savory.

Mostaccioli can be traced back to ancient Rome through the biscuit called mustaceos, recorded in Cato’s farming manual De Agricultura. The binding agent is musto, or grape must, today called mosto cotto, a syrup made from reduced grape juice that contains a degree of pulp, skins, stems and seeds, set aside from the wine making process. In a time before sugar, when honey collection was a laborious and potentially painful endeavor, mosto was a go-to sweetener, harbinger of good fortune and fertility. Another biscuit from the same period called mortarioli combined crushed almonds and honey. The ingredients in and the names of these recipes may have fused in time to become mostaccioli, a commonplace foodstuff by the Early Modern Era.

In the Renaissance, they are mentioned often as an ingredient to be crumbled into other recipes, which would have thickened sauces, added spice and texture to pies, or lent a caramel-toasted taste, resulting from the Maillard effect.

Renaissance chef Bartolomeo Scappi also lists them as a standard sideboard or antipasto item. Indeed, they seemed to be a rather ubiquitous staple.

Let’s start our trials in ancient Rome by checking out Cato’s recipe.

Mustaceos sic facito. Farinae siligineae modium unum musto conspargito. Anesum, cuminum, adipis P. II, casei libram, et de virga lauri deradito, eodem addito, et ubi definxeris, lauri folia subtus addito, cum coques.

Translation: Must biscuit recipe: Mix 1 modius of wheat flour with must; add anise, cumin, 2 pounds of lard, 1 pound of cheese, and the bark scraped from a laurel twig. When you have shaped them, put bay (laurel) leaves under them, and bake.

Standardized Version

Ingredients:

200g all purpose flour (or tipo 0)

80g must

1 tsp aniseed, crushed

1/2 tsp cumin, crushed

1 blade mace, crushed

5 tbsp lard

3 tbps grated pecorino romano

1/4 tsp salt

Fresh laurel leaves - N:B: You might think that this is an optional, but the aroma from the fresh leaves will impart a distinct flavor (as well as making your kitchen smell fantastic!). As we are not using them to create a separation between the food and the floor of a hearth, it is only necessary that each shape be placed on a leaf. If you cannot procure them, better to compensate with an additional blade of mace in the mix rather than use dried bay leaves.

Instructions:

Mix all of the ingredients except the laurel leaves.

Wrap the dough in plastic and leave to rest for 1/2 hour.

Place the dough on parchment paper in a rectangular shape. Roll it out and cut into rhomboidal shapes.

Lay a fresh bay/laurel leaf on each biscuit. Place another sheet of parchment on top and using a cookie baking sheet to assist you, flip the sheet over so that the leaves are on the underside. You can rig up whatever system works for you. The important thing is that each piece has a leaf under it.

Bake on an insulated baking sheet at 180° until starting to brown about 15 minutes.

Remove from oven and turn them over, leaf-side up.

Lower the heat to 100°, bake another 10 minutes.

Turn off the heat and keep the oven door ajar with a wooden spoon until they have cooled. Remove leaves before eating.

Set leaves

Flip the dough

Second baking

The tastes are intriguing and the mouth feel resulting from the lard was more-ish; I couldn’t stop eating them. Cato’s recipe does not specify the distinct rhomboidal shape that later became the calling card of these biscuits. The rhombus, found in artifacts dating back to the Neolithic era, is heavily charged with spiritual symbolism of eternity and the balance of male and female energy.

To decorate the biscuits more elaborately, households and convents had a personalized, engraved wooden stamps to emboss an image into the dough, like this one courtesy of food historian Sandra Inno:

As time went on, the recipes became sweeter and more heavily spiced, eventually dipping the cookies in chocolate, thereby passing into the dessert realm. The recipe below is less indulgent, a composite of recipes along the Renaissance timeline. They are neither too sweet nor too heavily spiced, lending themselves just as well to aperitifs as they do to an afternoon cup of tea.

Renaissance Mostaccioli - a composite recipe

Ingredients

45 g unsalted butter softened

75g/ 1/3 cup must

75g/ 1/3 cup honey

1 egg

300 g unbleached all-purpose flour (tipo 0)

1/4 teaspoon salt, preferably kosher slightly crushed

1/2 teaspoon ground cloves

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

40 g very finely chopped candied orange peel

120 g very finely chopped walnuts (but not to a flour)

Instructions

Design press

1. Mix wet and dry ingredients separately and then mix to make a dough.

2. The dough will be sticky. turn out onto a sheet of parchment paper.

3. Spread it out with your hands in a rectangular shape, sprinkling with flour.

4. Roll out with a rolling pin, sprinkling with flour, trying to keep a rectangular shape.

5. Make about 3mm thick.

6. Press some sort of decorative design into it. I used a gnocchi board.

7. Cut into 2-bite rhomboidal shapes.

8. Place the parchment on a baking sheet.

Classic shape

9. Bake for 15 min in a 180° oven

10. Remove. Turn the oven down to 100°

11. Cut and separate the pieces when cool enough to handle.

12. Flip the pieces over and return to the oven for another 15 min.

13. Open once to release steam (if your oven sucks like mine).

14. Remove the tray and flip them over right side up and bake another 15 min.

15. Prop the oven door open with a wooden spoon and leave to cool.

La Singolar Dottrina di M. Domenico Romoli detto Panonto (or variously Panunto) (1660) has left us a recipe entitled “How to make another sort of Mustaccioli.” This is decidedly sweeter, and has the characteristic aroma of rosewater that was splashed onto a vast array of dishes on the aristocratic table. What is curious is how the ingredient, mosto, from which it gets its name, had become superfluous.

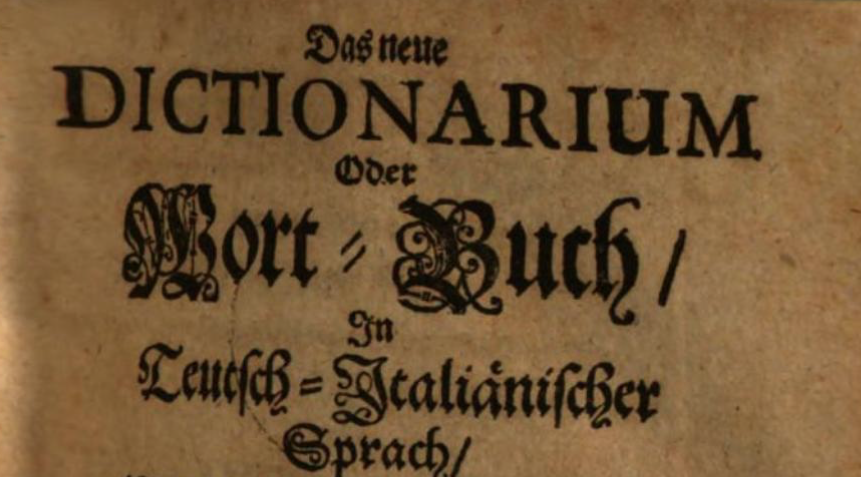

I stewed at length over the archaic dialectal word gengeuere also written gengevro. Unreliable sources have translated it as both “ginger” and “juniper” and I myself had oscillated anxiously between the two. But I finally found reassurance in a German-Italian dictionary from 1678:

And I settled on the powdered form as it is in a list of other dried spices.

While you prepare them, you may want to muse over the tempestuous times during the reign of Pope Leo X, whom Romoli served as steward. After news of Martin Luther’s Ninety-five Theses hit, one would surely have needed a restorative biscuit.

Romoli’s Mustaccioli

Ingredients

55g/80ml/1/4 cup rosewater

140g/ 3/4 cup sugar

1 tsp ground cinnamon

1/4 tsp each powdered ginger, pepper, cloves, nutmeg

200g (about) all purpose flour

4 tbsp butter (not in original)

Instructions

Rosewater Mustaccioli

Preheat oven to 180°C

Combine the rose water, sugar and spices in a medium sized bowl.

Add half of the flour and mix vigorously with a spoon.

If you would like these to go easier on the teeth, here’s where you add the butter.

Add the rest of the flour until you cannot stir it anymore, then turn it out onto the countertop.

Continue kneading in flour until you have a not-too-soft workable dough, something that you can reasonably roll out without it being too sticky or too dry.

Place the dough onto a piece of parchment paper in a rectangular shape.

Role out the dough, flouring as little as possible, until it is cracker thickness.

Cut rhomboidal shapes.

Put the parchment on an insulated cookie sheet and bake 10-15 minutes. These are more delicate than the previous recipes.

Remove the cookies and separate each one. They will fuse together during baking.

Turn the oven off. Put them back in the oven keeping the door ajar with a wooden spoon until they have cooled.